NIGHTHAWKING: The Dirty Side of UK Metal Detecting

Metal detecting occupies a strange and beautiful corner of British life. It is, at its heart, an act of patience: a slow walk across a field, a conversation with the soil, a search for quiet echoes of the people who lived before us. When done properly, it is a partnership between landowners, detectorists, archaeologists and the local history of a place. It is built on trust, curiosity and care.

And then, trampling through that carefully tended relationship like a fox in the henhouse, comes nighthawking: the illegal, destructive, reputation-shredding underbelly that detectorists despise, farmers fear and the public barely understands.

To understand why nighthawking is such a stain on the hobby, you have to start with what responsible detecting actually means. It involves permission asked and granted. It involves tidy digging, careful recording, respect for Scheduled Monuments and legal obligations under the Treasure Act. It is slower than people think, more thoughtful than they assume, and far more rooted in stewardship than in treasure-hunting.

Nighthawking is the opposite of all of this. It is greed dressed up as adventure; crime disguised as curiosity.

A nighthawk operates under the assumption that night and distance will hide the damage. A field gate left open at midnight. A torch beam sweeping across ridge and furrow like a scalpel. A car parked half in a ditch. The sound of hurried digging. And then they’re gone, leaving behind nothing but holes, damaged archaeology and a landowner who will awaken to the sight of vandalism in the morning light.

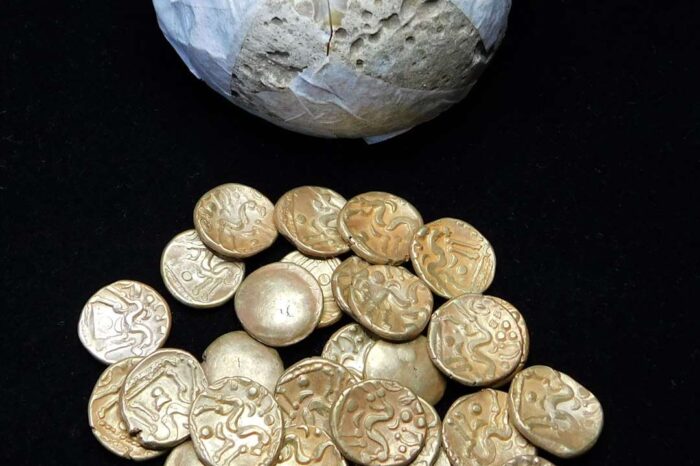

What nighthawks steal is not simply metal. They steal the context that gives an object meaning. Archaeologists know this better than anyone: remove an artefact without recording its place, its depth, its surroundings, and you have torn out the heart of its story. A Roman brooch taken from a Scheduled Monument in the dark is not merely theft; it is a small act of historical amputation. The story it belonged to is now broken, perhaps beyond repair.

And the consequences ripple outward.

A farmer who finds fresh holes in their land is unlikely to welcome another detectorist, no matter how polite, responsible or well-meaning. A museum robbed of a potential find never gets the chance to share it with the public. A local community loses another clue to its past. And every detectorist who tries to do things right carries the weight of suspicion left behind by someone else’s wrongdoing.

Nighthawking thrives in the same way all quiet crimes do—through isolation, opportunity and the knowledge that rural policing is stretched thin. Archaeological sites that should be protected become midnight playgrounds for people willing to gamble their future for a few coins sold anonymously online. The heritage crime units do what they can, and occasionally a nighthawk is caught and prosecuted. But for every conviction, there are dozens who slip through the cracks.

It creates an emotional toll in the community, too. Detectorists who spend their evenings logging finds with the Portable Antiquities Scheme see their efforts undermined. Volunteers who contribute to archaeology feel betrayed. Farmers who once enjoyed seeing what their land produced now find themselves installing cameras and motion sensors. And behind all this lies an unspoken truth: one nighthawk can ruin a relationship that took years to build.

Yet the most infuriating thing is this: nighthawks rely on the hard work of others. They target the fields that detectorists have researched honestly. They go to the sites they’ve seen responsible detectorists walk to. They watch social media, map photos, festival events and club rallies. They hide in the shadows of the work done by people who follow the rules.

This is why detectorists loathe them more than anyone else does. Farmers see trespassers. Archaeologists see lost data. Police see another complaint on a long list.

Detectorists see the destruction of their reputation.

And yet, despite the anger, there is something else emerging within the hobby: unity.

The community is becoming sharper, more vigilant, more connected. Farmers and detectorists now talk openly about suspected activity. Social media groups call out dodgy behaviour. Clubs tighten their codes of conduct. Training courses emphasise legality and responsibility. And detectorists who once felt alone on their permissions now feel part of a wider effort to protect British heritage from those who want to steal it.

The truth is simple but powerful: responsible detectorists are the strongest weapon against nighthawking. They are the eyes in the fields, the trusted partners of landowners, the people who know every hedgerow and access point. They are the ones whose early-morning routines often expose midnight trespass. They report what they see, they challenge what they suspect and they help shape a culture where secrecy and greed cannot flourish so easily.

It is too easy to dismiss nighthawking as an inevitable part of the hobby. It is not. It is a choice, made by a very small minority, to harm the land, steal the past and poison a community that works incredibly hard to do the opposite.

The vast majority of detectorists do not just dislike nighthawks; they make every effort to undo the damage they cause.

And that is why, despite everything, the hobby endures. Trust can be rebuilt. Permissions can be restored. Land can heal. But only if the voices of responsibility stay louder than the shovels in the dark.

History belongs to everyone. But only if everyone deserves it.